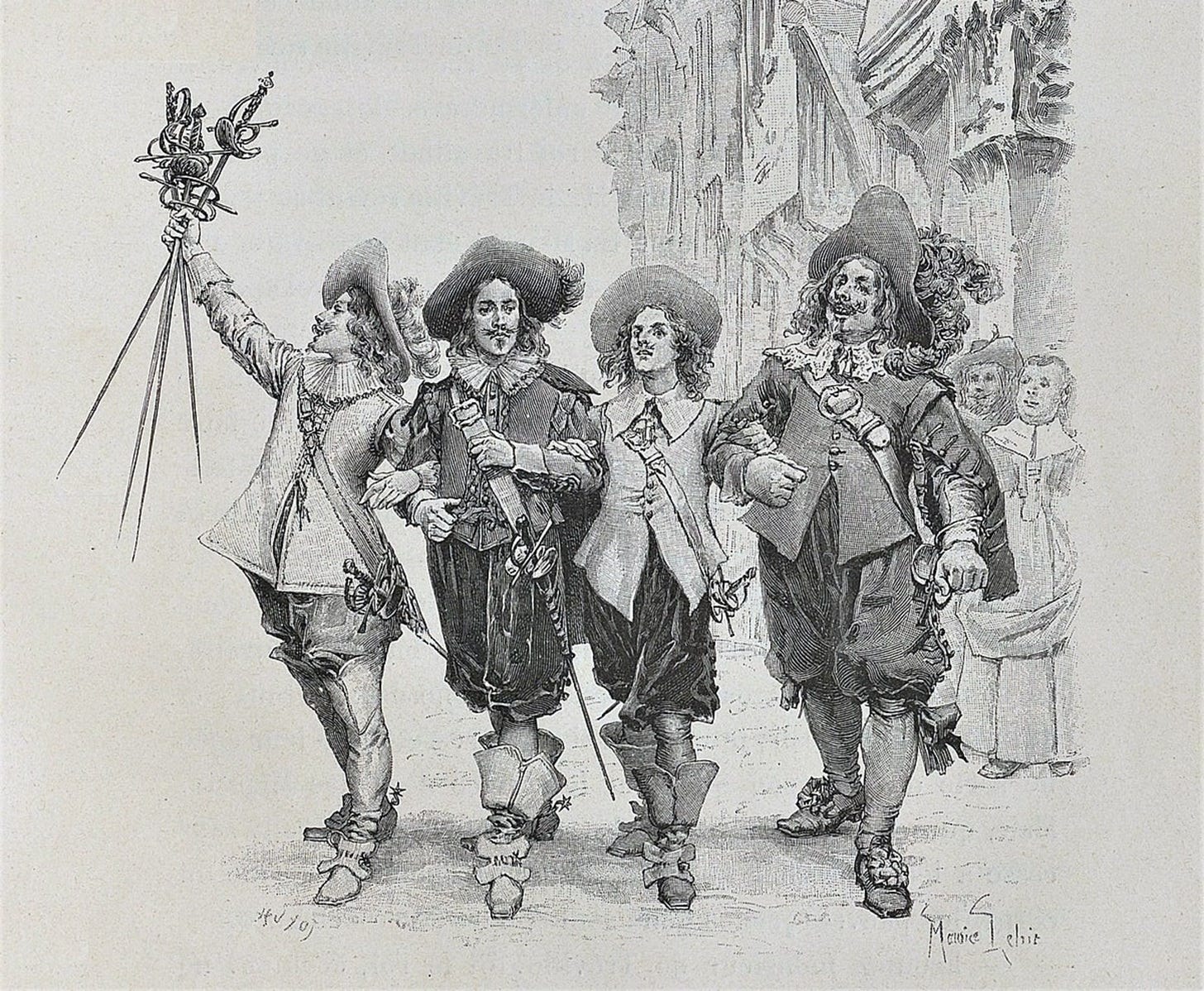

When Alexandre Dumas wrote that phrase in his book The Three Musketeers in the 19th century, he was referring to the bond of unity and solidarity that the musketeers swore to one another. It was a version of the we’re “better together” adage. Similarly, I wrote in a previous post that the importance of community and belonging was central to those living in Scandinavia during the Viking Age (c.750-1100 AD) and maybe something we need to revisit in our modern lives. The basic premise being, should we think of the community, or should self-preservation come first?

I’ve wondered about this a lot.

When teaching about the historical shift from the Middle Ages (which was inherently more concerned with the collective) to the Modern Era (which was built on Enlightenment individualism, at least for western countries), I used to ask my students which condition they thought was more natural for human beings. Do we care more for others in our community, or are we primarily out for ourselves? Do we tend to be more compassionate or more greedy? Or, if we are compassionate, is it a luxury emotion, meaning it only gets expressed when all my needs have been met and then once safe and content, I can think about your needs?

The questions always sparked a lively and thought-provoking discussion. My students’ immediate, knee-jerk reaction to the question of greed versus compassion always resulted in a resounding “people are GREEDY!” But then we’d talk it through, and though it generally ended in the same conclusion, it was always tempered by the admission that even though we think our default is to be self-serving, students conceded that we should probably try harder to work together and be a little bit more compassionate because that was important too.

It is a well-established fact that it’s important because humans are a social species; many studies have long shown that we flourish with others around to care for and who care for us, and we seem to struggle when isolated. One only has to look at the current state of affairs in the world — especially since the advent of social media — to see that even though we have access to connection with more people in the world than humans have ever had in our entire history, we seem to exist in little bubbles and echo chambers that keep us separate from each other and not connecting in meaningful ways. And this is a condition that has only been made worse since the Covid pandemic, making the combination of the two a perfect storm of negative effects from anxiety and depression to loneliness and self-harm.

However, as someone who certainly has introvert tendencies, I’ll admit to struggling with this idea of always “better together” a bit. I am not a hermit, nor do I want to be (though I did write my graduate thesis on life in a monastery….), but I’ll admit that Covid lockdowns were kind of a welcome breeze for me. The ability to work on my own from home and get done what I needed to without the interruption of senseless meetings and hours spent commuting in my car was like a gift. I and introverts the world over collectively breathed a sigh of relief at not having forced interaction with others on a daily basis. I have always been an independent person, and frankly I thrive when I’m self-directed and able to just get on with things without the distraction that other humans bring.

Additionally, I come by this attitude not just because I’m an introvert, but because I’m also a product of where I was born. It’s no secret that American culture loves the fable of the “self-made man.” The country was built on independence and the idea that everyone has the promise to “pull themselves up by their boot straps” and create their own destiny. We even sort of collectively look down on people who don’t pull their own weight and need to rely on others. A common phrase uttered by both my grandparents and my parents when I was a kid was, “charity begins at home,” a clear statement of me/us first, then (maybe) others. So, in some ways I was raised in a context that values encouraging people to get on with things solo. But does this, ergo, mean I’m greedy and not compassionate? Of course not. I’ve never thought of it as an either/or proposition.

I believe the “American Way” is only partly positive at best. While the hyper-competitive, go-it-alone, pioneer mentality can (and has) create interesting breakthroughs for humanity to be sure, it can also create negative outcomes in encouraging people to chase success, wealth, power, and influence at all costs — often at the expense of others.

If we’re being honest, we know full well that anyone who has ever achieved anything — myself included — did not do it alone. As the saying goes, it really does take a village. Though I am strong and self-motivated, there have been countless teachers, mentors, friends, and family members without whose support and guidance I would not be where and who I am today. And for them I am eternally grateful.

While doing some research just the other day, I found the economist Thorstein Veblen had something pretty definitive to say about this question of humans going it alone, which he put rather bluntly in an essay where he was criticizing the “natural rights” theory of classical economists:

This natural-rights theory of property makes the creative effort of an isolated, self-sufficing individual the basis of the ownership vested in him. In so doing it overlooks the fact that there is no isolated, self-sufficing individual. All production is, in fact, a production in and by the help of the community.

And he went on to say…

Even where there is no mechanical cooperation, men are always guided by the experience of others. The only possible exceptions to this rule are those instances of lost or cast-off children nourished by wild beasts, of which half-authenticated accounts have gained currency from time to time.

Veblen’s wry wit — which I love — is evident in that last part. But his point is clear: we need each other even to the extent that when people aren’t physically helping us, they most certainly are mentally in that their advice and previous experiences provide guideposts for us. So, others are with us all the time, and it’s that fact which makes what we achieve possible. As a matter of biology, our species evolved to need others because existing at all was only possible because of the contributions of many. But even now in the modern West, where we may not live subsistence lives like those of medieval peasants, our need for others still exists though has arguably evolved into more social and emotional support — friendship, comradery, love — all things also necessary for us to thrive.

That being said, I’m still unsure if there’s a clear answer to the “better together” proposition. I think it seems like it’s a challenge for us most of the time to prioritize other people. Just today, for example, my husband and I were driving home from the grocery store. We were on a through street and I noticed someone parked in the lane directly in our way. As we came upon them, they slooooooowly began to move their car forward and then sort of stalled and acted like they didn’t know what they intended to do next. They then made a slow left hand turn with no blinker, appearing to have no regard for the fact that they were holding up others on a very busy street. They were lost in their own head, thoughts, reality, whatever, and not seeming to care that they were inconveniencing people. Now, of course in the grand scheme of things, this was just a very minor frustration to be sure. So here’s another example.

In my town, the homeless population has increased in recent years and become a very contentious issue. While there are many who have compassion for them because they often suffer from issues such as mental health problems, many more of the homeless suffer from addiction which leads to them living outside, often in unsafe, unsanitary conditions that are in thoroughfares used by the rest of the community, and most of them refuse shelter saying they prefer to stay on the streets — often because shelter requires them to get sober/clean. In this situation we have seen compassion from the community reach its limits. People are tired of seeing the homeless pitching tents in their neighborhoods, urinating and defecating in their yards, and openly using drugs. They are also tired of having to keep their children safe from it and experiencing the crime that accompanies it. Our evolutionary need to have care and concern for others in the community has eroded to the point where people have become more interested in just making the problem go away. Is the desire to protect one’s own home or neighborhood from such a menace simply self-interested behavior? Or should there always be more collective care for everyone in the community regardless?

These two examples raise some serious questions: If we all thrive when there’s solidarity, unity, and concern for others, then why do we not act like that all of the time? Why do we resort to “me first” thinking, and then take it even further and get into conflicts and wars with each other? If we’re so biologically hardwired to care in order to survive, doesn’t self-interest and going it alone make our destruction inevitable?

As we appear to be entering into a new phase of history where countries are intensely competing with and antagonistic toward each other, and further choosing isolationism as a strategy, where does that leave us in a globalized world? Why, exactly, should one claim to be an individual island in a world of billions? How is that going to work?

It seems humans need but can only stand each other for so long. We like to get together but then also crave some space to be alone. And perhaps this is the paradox of being human. This is why I believe this conundrum is not an either/or proposition, but rather it’s a both/and. Though those are opposing conditions, we need both to really flourish. But there must be a balance. We can think of ourselves, but we must also think of others because we don’t exist in a vacuum.

George Costanza was right.

For most of human existence we, like all creatures, have lived in a world where scarcity looms over us, perhaps not in this moment, but will we bump into it around the next bend?

Who will help us when famine, poverty, or illness barge into our lives? Admittedly, I have not studied this, so I'm venturing out on a frozen lake in April here, but I suspect the answer is, those who are closest to us - those who are part of our "community" (however we define it).

There are many situations where banding as a community helps: "We will together guard our flocks of animals and the scarce grazing land from other communities. There is not enough for everyone, so it's us or them!" Charity and support to some, but not others, was part of survival.

It is brutally callous to ask this, but while the un-housed population you mention in your post live in your city, are the part of the "community?" Do they contribute something of value to the rest of the community? If the community cannot see value in having them be part of the community, then it is likely they will be perceived to be "outsiders" and unwelcome.

I'm not sure this is greed; I think it is part of human fabric, woven by the savage realities of evolution in a hostile world.

Perhaps community is shrinking in this day and age, because our survival does not depend on it much anymore. As C.J. points out in his comment, when survival is threatened, we can suddenly come together - community suddenly matters. Does our happiness depend on community? Your post suggests "yes," and I agree.

My view is rather bleak and perhaps raises the question of how then do I explain the actions of some people who step outside of their communities to run soup kitchens, shelters, and out reach programs? Why are they helping those outside their community? I don't yet have a good answer to that, but maybe I will not look too closely because I really want to believe they are expressing another behaviour that, if we are lucky, is inherent in humans. One that may help us live on this increasingly stressed earth together.

Great article. It reminds me of something I encountered in a book recently. The name of the sociologist is escaping me at the moment, but the proposition was that humans really only work well together in large groups when faced with a common external threat. Think of the social cohesion of the greatest generation during WW2, and thereafter, contrasted by the individualism of the Baby Boomers and then hyper-individualism of gen X’ers, and so on. If we roll the clock back to pre-civilization, cooperation was fundamental to survival. But now that we’re all fat and comfortable, it’s just not worth the effort in most cases. It appears to be a learned behavior that, removed from its original context, doesn’t make much sense to us, but then again is foundational to our way of life because even though things are comfy now, they’re comfy because people worked together to make it that way. Great food for thought, thanks Terri! 😊