If you’re not familiar with Denmark, you probably don’t know what an utterly watery place it is. Part of it is attached to and juts out from the European Continent — appropriately named Jutland (Jylland in Danish), but the rest of it is a bunch of archipelagos. As the oft-quoted statistic goes, “Wherever you are in Denmark, you are no farther than 30 miles to the sea.”

This place is, and always has been, defined by water, and so it shouldn’t surprise you that it was no different during the Viking Age (c. 750-1100 CE). As a matter of fact, Scandinavia was even more watery back then than it is now. Thanks to climate change and the melting of glaciers and runoff, the release of weight from ice melt has meant that the land has actually risen and become exposed in many places that were underwater 1,000 years ago.

So when you think of Vikings and a longship instantly comes to mind, you can’t be blamed. There’s a good reason for that. There is no more iconic image for the period because it was a marvel in technology and craft that enabled survival in that fluid world. But let’s not forget that for many it was also a symbol of the terror to come once spotted in the waters nearby. No doubt about it, in many ways ships were critically important both in life and in death.

To get a good sense of this, let me tell you about a couple sites I’ve had the good fortune to visit in the past couple days.

First, was the ship museum at Roskilde. An amazing place where people can see the remains of five ships from the Viking Age that were discovered and raised from the nearby harbor in the 1950s, as well as the active workshop of experimental archaeologists who are practicing the traditional skills of boat building to learn about methods from the past and educate the public about them. The museum was yet another example of the way the Danes excel at making their past accessible.

While the Viking warship/longship is probably the most commonly recognized, the Scandinavians actually built several types of vessel during the Viking Age from simple dugout canoes to fishing boats, to medium and large-sized cargo ships. The artifacts at the museum, artfully recreated in “full size” out of the surviving remnants, give a good sense of these different types.

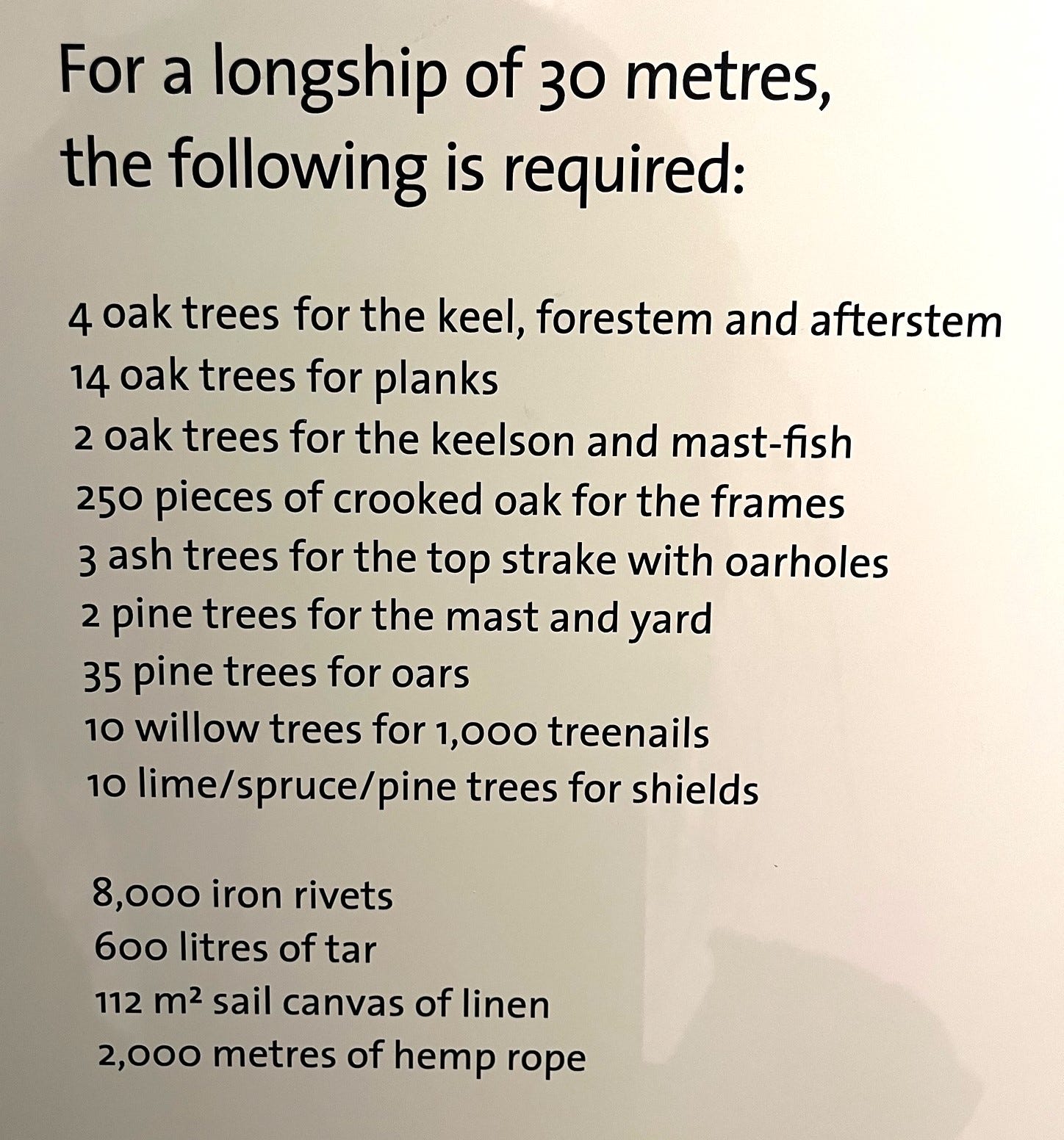

Viking Age builders were known to prefer oak, and green oak at that so that the moisture in the wood fiber made it easier to bend long planks into shape. But they also used other types of wood as well. This sign, posted at Roskilde, gives a sense of the required woods for just one ship roughly 100 feet in length:

Rather than marrying the boards one next to each other and fastening them to a frame to hold them together, they overlapped the boards in a manner known as “clinker” building and nailed them together using iron rivets, many of which have been uncovered from Viking Age sites. The gaps between planks were often further sealed with tar to make them water tight.

The surviving bits of planks, keels, masts, ribs, and stemposts at Roskilde, even though not complete, still provide important information about how the wood was hewn and how these ships were masterfully assembled.

The other thing that archaeologists and historians believe set the Scandinavians apart during the Viking Age was the use of larger masts beginning some time in the 8th century. This allowed for larger sails and therefore more locomotion (beyond oars), particularly out in the open sea. The sails were a major feat in craftwork and were often held as more valuable than the ships themselves. Because textile work of all kinds was typically done by women (both free and unfree), it is believed this was true for the ship sails as well.

To give you a sense of how labor intensive just this one aspect of a Viking ship would have been, archaeologists have estimated (based on the Ladby ship, an early-10th century ship found in Denmark, which I’ll be visiting next week) that to make a sail of 61 square meters (32x20 feet) the number of hours of spinning and weaving it would take one person to complete is just over 4,100. This is working 12 hours per day for almost a year. Sails were generally made of wool (but could be made of other fibers) and treated with tar or animal fat to make them weather and water resistant. If you’re interested in more information, check out this 32-minute video featuring archaeologist Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson from Uppsala University in Sweden who explains the various components of a Viking ship.

The ship motif was so prevalent in Viking societies that even longhouses were often constructed in the same general shape, with bowed out exterior walls and a roof ridge line that resembled the keel of a boat turned upside down, such as in this example we found at the Fyrkat Fortress in Hobro, Denmark.

In addition to using ships for warfare, trade, and fishing, Scandinavians during the Viking Age also knew the ship as a powerful symbol for transportation into the next world after death. Primarily in the period before Christianity came to the North (around the year 1,000) the ship was used in burial, both literally and figuratively.

We’ve all seen the Hollywood “burning boat” trope for a Viking funeral, which was true for only a very few, but to be cremated and then have your remains buried in the ground with stone markers placed in the shape of a ship was a bit more common in some places. One such place was Lindholm Høje, the site of several hundred burials in northern Jutland, Denmark. It has long been a site I’ve wanted to see. In true Viking fashion, the ancestors were kept close and remembered, and for me spending time in their presence was magical and humbling.

Lindholm Høje (høje is the Danish word for “hill”) was inhabited and in use as a cemetery for several centuries, pre-dating and including the Viking Age. Archaeologists have found a village nearby that dates to the Viking era. This is when the stone ship settings proliferated. They stopped being used once Christianity took hold in Denmark toward the end of the 10th century, when inhumation rather than cremation and burial in consecrated ground near the church became the norm.

The preserved burial site is now separated from the village location by a grove of trees. I don’t know if a grove was there 1,000 years ago, but I’d like to think there was because surviving evidence tells us that tree groves were often sacred places for pre-Christian Scandinavian peoples.

We walked the path through the trees and up over the hill to see the multitude of stones laid out before us as the final resting place for men, women, and children. Smaller, round settings were generally the burials of women and children, while the ship shape with two pointed ends was reserved for men. In addition to being burial sites, we also know that sometimes these same ship settings in stone were used as property markers to define boundaries. And sometimes these were very intentionally laid out with what can be identified as the prow of the ship facing in the direction of the nearest water source such as a river or bay.

For this historian, these two sites were great reminders that the iconic Viking ship is not just the stuff of movies. For Scandinavians at the time, a life on the water that surrounded them in every direction was natural and normal. Even as I write this, I glance up and look out at the harbor in Aarhus. In the same view I see ferries, sailboats, rowers, tugboats, and giant container ships. As they were 1,000 years ago, the ships that have come to define the Vikings and their Age remain a crucial part of life in Denmark today.